In the early 1970s, it could be said that the Twin Cities of Minneapolis-St. Paul and the surrounding region offered it all when it came to opportunities for young instrumentalists who were seriously interested in playing the symphonic repertoire. Unlike most American metropolitan areas of similar population, the Twin Cities metro area was home to not one … not two … but four private youth orchestras. These organizations attracted the cream of the high-school instrumental talent, drawing participants from a 75-mile radius around the Twin Cities.

Ready access to multiple youth orchestras boasting high artistic standards and selective admissions made it a challenge for secondary school music programs to measure up in comparison. For serious instrumentalists — those contemplating conservatory educations and careers as professional musicians — it was only natural that their best efforts and energies would gravitate to the private programs.

In 1973, a confluence of organizational changes involving the top four Twin Cities-area private youth orchestra organizations resulted the formulation of a grand plan to establish a single, unified private organization — one that would work closely with the music educators in the public schools to minimize competition and scheduling conflicts while buttressing the school programs by requiring student participation in school orchestras as a prerequisite for membership in an outside youth orchestra organization.

At the end of the 1971-72 school season, the four youth orchestras, including the Metropolitan Youth Orchestra, the Minneapolis Youth Orchestra, Saint Paul Youth Orchestra and the MacPhail Youth Orchestra, ceased operations. In their place emerged the Greater Twin Cities Youth Symphonies (GTCYS), consisting of several ensembles (based primarily on age).

Significantly, GTCYS adopted a policy that required its members to take part in their school orchestra or band programs, while on the GTCYS board sat members of the Twin Cities music education community who were also officers and members of the Minnesota Music Educators Association (the Minnesota chapter of the Music Educators National Conference).

With the formation of GTCYS, the vision of realizing one single outside-of-school youth orchestra organization was complete. Except …

Not everyone was on board with the new vision. Among the four original organizations, the Saint Paul Youth Orchestra stood out. It was one that took its mission to deliver a true pre-professional orchestra experience the most seriously. Its music director, Ralph Winkler, was a violinist with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra as well as a conductor who had high expectations of his players and insisted on diligent effort and quality performance.

Under Winkler’s leadership, the Saint Paul Youth Orchestra prided itself on playing complete works (not selected movements or excerpts) from the actual composer scores (not simplified versions adapted for student orchestras). The entire performing experience was approached in the same manner as professional orchestras — from repertoire selection and rehearsals to concert attire and overall musician comportment.

Not wishing to lose those special qualities, a sizable contingent of former Saint Paul Youth Orchestra students and their parents implored Winkler to form a successor youth orchestra organization that would carry on the high standards that had been set by the old Saint Paul Youth Orchestra.

Accordingly, a new organization was formed as the Minnesota Youth Symphony (MYS) and began its first season in the fall of 1972.

The blowback from the public school music education establishment was immediate and fierce, reaching into every corner of the Twin Cities-area music community. Even before fall rehearsals could commence for the MYS, it found itself barred from using rehearsal spaces that would normally have been made available without hesitation. It was only after a frantic 11th hour search that a makeshift space for rehearsing could be found at Augsburg College, a private institution.

Concurrently, students joining MYS faced overt hostility from their public school music educators. Students playing on school-issued instruments were informed that they could no longer take their instruments home on weekends. Other MYS members were threatened with refusal to provide letters of recommendation to universities and conservatories — or worse, threatened with grade demotions if their activities with the MYS conflicted in any way with school orchestra activities happening outside of regular school hours.

For any student who was serious about embarking on a performing arts career, the possible repercussions were ominous.

Undaunted by these setbacks, the MYS began its inaugural season with a fall concert that included, among other works, Beethoven’s Fidelio Overture and Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis, followed by a winter concert that included Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4 and two spring concerts that featured works such as Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kijé Suite, Sibelius’ Swan of Tuonela, Copland’s El Salón México and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

The extraordinary quality of playing of the nascent orchestra was such that the MYS was selected by American Youth Performs to tour Romania during the summer of 1973. Such an undertaking would require substantial fundraising on the part of MYS students, families and friends.

Throughout the period of intensive fundraising activity that followed, the MYS faced relentless criticism and unfounded ethical allegations that were communicated to prospective donors, foundations, and even American Youth Performs in New York, the tour organizer. Once again the MYS overcame these hurdles, embarking on a successful tour and playing in the concert halls of the largest cities in Romania including Bucharest, Timisoara, Cluj, Sibiu, Iasi and Constanta.

Throughout the period of intensive fundraising activity that followed, the MYS faced relentless criticism and unfounded ethical allegations that were communicated to prospective donors, foundations, and even American Youth Performs in New York, the tour organizer. Once again the MYS overcame these hurdles, embarking on a successful tour and playing in the concert halls of the largest cities in Romania including Bucharest, Timisoara, Cluj, Sibiu, Iasi and Constanta.

Back home in Minnesota, the drumbeat of hostility continued relentlessly from official MMEA quarters as well as from a group of co-conspirators associated with secondary and collegiate-level public music education. In 1973, the MMEA condemned MYS within the context of a resolution titled “Concerning Extra-Curricular Musical Organizations and Their Relationship with School Instrumental Programs.” In 1975, a similar, slightly amended version was passed that reaffirmed the 1973 resolution.

To the MYS staff, students and their parents, the message had become painfully clear: The MMEA’s intention was nothing less than the obliteration of the one youth orchestra that had dared to exist outside of the “approved” structure.

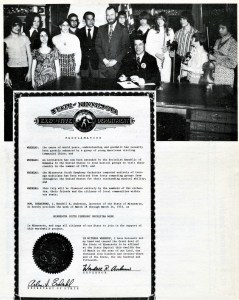

The sober realization was that relief could come only from legal action. In 1975, the MYS filed suit against the MMEA, citing a litany of actions directed against the organization and contending that these comprised violations of students’ constitutional rights involving the first and fourteenth amendments.

The MYS was joined in its legal action by the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union, which agreed that serious violations had occurred.

There followed two long years of litigation involving many hours of discovery, interrogatories and depositions (along with a failed motion by the defendants for summary judgment), cumulatively amassing several thousand pages of documentation.

But in the end, the result was complete vindication for the MYS, its staff and student members, which prevailed on every count. The Final Judgment handed down by Federal Judge Earl J. Larson on September 22, 1977 was a clear victory for students’ constitutional freedoms. (The Final Judgment can be read in its entirety here.)

In the years and decades that have followed the 1977 legal victory, the MYS has flourished as one of America’s leading youth orchestra organizations. Over the years it has benefited from a close (if unofficial) association with the Minnesota Orchestra; two of its music directors, Clyn Dee Barris and Manuel ‘Manny’ Laureano, have come from that orchestra, and numerous Minnesota Orchestra musicians have supported the MYS as sectional coaches.

Known today as the Minnesota Youth Symphonies, the organization is many times larger than in its early years, and it remains firmly established as a respected arts organization serving the Twin Cities and the surrounding region.

Its artistic vision is little changed from the early days, with a continuing focus on presenting the best in classical music, including performances of some of the most challenging works in the orchestral repertoire such as Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 and Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps.

Undoubtedly, few if any current students or their parents know that the freedoms they take for granted without a second thought were at one time under attack in a concerted assault that very nearly killed off the orchestra in its infancy.

Squaring the circle — and contrary to the fears of the MMEA and like-minded educators back in those early days — both the Minnesota Youth Symphonies and the Greater Twin Cities Youth Symphonies have found success in their missions and in working closely with school music programs. Relations between the MYS and GTCYS have been cordial for decades, and the orchestras have occasionally collaborated in joint performances.

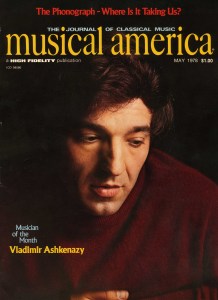

Of course, this is how it should be. But at one time, such an outcome seemed fanciful at best. As the music journalist Charles B. Fowler wrote in the pages of High Fidelity/Musical America magazine in May 1978, in the months after the lawsuit was settled:

Of course, this is how it should be. But at one time, such an outcome seemed fanciful at best. As the music journalist Charles B. Fowler wrote in the pages of High Fidelity/Musical America magazine in May 1978, in the months after the lawsuit was settled:

“Such infighting is damaging to the music teaching profession and to the arts in general. By their lack of magnanimity these music teachers debased their own kind. But who loses the most? The students. Such tension and strife distract the learner and detract from the learning situation. Energies are misdirected. It’s a bad lesson in human relations.”

Thankfully, the story has a happy ending. In the days following the Final Judgment, word spread rapidly throughout the music education community across the country. Other private organizations came forward detailing their own accounts of experiencing hostility and harassment at the hands of the music education establishment. The Minnesota court decision, coupled with the ugly realization that such abusive actions had been happening in other places, changed the atmosphere almost immediately. Indeed, it was akin to lancing a boil.

But as with all happy endings, we mustn’t forget the lessons learned along the way. It’s important that history marks the time when ethical standards in music education reached a low point. As Fowler wrote in 1978 — in words that matter still today:

“Music is by no means an assured route to humanism. Generosity, love, esteem, honesty, appropriateness, forthrightness, integrity — these are traits as much apart from the arts as the sciences. At times the arts may reflect them, but the human being — even those in the closest association with music — may simply choose to look the other way.”